Culture at a Click: Banglanatak dot com in partnership with Google Arts & Culture launches online exhibits on Bengal Patachitra and Purulia Chau.

We are a social enterprise working for the safeguarding and revitalization of traditional art forms for more than 15 years. Our flagship initiative Art for Life (AFL) builds sustainable eco systems for community led safeguarding of Intangible Cultural Heritage. AFL promotes Village, Artist, and Art together and has evolved the process of art and culture led rural development.

Our repository has images, videos and well researched stories of performing art and craft traditions across India. We are partnering with Google Arts & Culture to share about the intangible cultural heritage of diverse communities across India with over 1500 visuals on the crafts and performing arts of Bengal, Rajasthan, Jharkhand, Arunachal Pradesh, Bihar, Nagaland, Maharashtra from our archives that can be viewed online by people around the world. And there can be no better partner than Google Arts & Culture for this virtual exhibition.

Google Arts & Culture is the online platform to explore art, history and the wonders of the world in an immersive manner, all with just a click on your phone or computer. They develop technologies that help preserve and share culture and allow curators to create engaging exhibitions online and offline, inside museums. The Google Arts & Culture app is free and available online for iOS and Android.

Short summaries of our stories

Goddess Kali: The Transcendent Deity

https://artsandculture.google.com/story/1QXhmksCMSHqpA?hl=en

Goddess Kali is widely worshipped during Diwali in the Eastern region of India. Kali has been diversely represented in the different art forms of India; the diverse representation reminds us of the myriad socio-cultural fabric of our country. Sometimes Kali is represented as a fierce warrior and sometimes as a loving mother. Alongside being the Goddess of darkness, destruction, and death, Kali is also a symbol of Mother Nature because she is believed to be timeless and formless, representing the creation of life and the universe as well. Through our exhibit on Kali we have tried to capture this depiction of Kali and also the iconography behind the images. The iconography has been presented with significance of the images of Kali- the dark skin, weapons in her hand, her tongue sticking out, her mount-fox. The rituals involving Goddess Kali in art forms like Gomira and Sholacraft of Dinajpur districts in West Bengal have also been lucidly incorporated to make the story more informative and appealing.

Diwali: Celebration of Light and Hope

https://artsandculture.google.com/story/6wURs_CpTpbeGg?hl=en

The exhibit on Diwali perfectly captures the festive mood. Goddess Lakshmi, the Goddess of wealth and prosperity is worshipped on Diwali and that has been beautifully portrayed in the story with art forms like Patachitra, Dokra and Wooden Doll of Bengal. Lighting up homes and hearts of Indians, Diwali is a celebration of the triumph of light over darkness and is known for heralding positive beginnings. To symbolize the victory of light over darkness, good over evil and knowledge over ignorance, lighting of lamps is a common practice in Diwali.That makes it a festival of lights, and beautiful handcrafted lamps adorn Indian homes during this time. The exhibit shows some of the intricately handcrafted diyar by the Dokra artists of Bikna. One can also find eco-friendly options of lights like Terracotta, Sholacraft which are not only beautiful but also environment conscious option.

Durga in Bengal Patachitra

https://artsandculture.google.com/story/GwWRMLuOLSz37Q?hl=en

Patachitra is a unique storytelling tradition of Bengal where the artists known as Patuas paint stories on long scrolls and narrate these stories in the form of a song. Goddess Durga, the most popular local deity is an important subject of their composition. The exhibit showcases how Patuas of Naya village of Paschim Medinipur district of West Bengal depict the story of Goddess Durga. In the exhibit one can see some beautiful Patachitra paintings of Durga as represented by the Patuas. It is interesting to notice the diverse representation of Durga by the artists, some portray Durga as a Goddess combatting the evil forces and some depict the Goddess as a loving mother.

Patachitra in Durga Puja Festival

https://artsandculture.google.com/story/rAVxYXl3CHiYow?hl=en

This exhibit gives an overview of how the unique storytelling tradition of Bengal Patachitra has merged with the celebration of Durga Puja in Kolkata. Here one can see the beautiful artworks of Patachitra adorning pandals, as well as the idol. Each pandal becomes a public art installation. The exhibit showcases Patachitra art on Durga idol, pandal, as well as celebration of the festival itself through paintings.

Experiencing Purulia Chau

https://artsandculture.google.com/story/dQVx1xL9etTmUw?hl=en

This exhibit introduces the various facets of the Purulia Chau dance – the dance form, the palas or dance dramas, the steps, the artists and the musical instruments. The folk-art form is a brilliant combination of acrobatic dance, ornate masks and costumes along with Jhumur song and rhythmic beats. The exhibit provides an immersive experience of the land of red lateritic soils, the vibrant dance, soundscapes of unique instruments and the craft of mask-making that will transport you to the rustic land of Purulia. This exhibit is the perfect combination of information and entertainment that gives an overview of the traditional art form that has gained popularity among international audiences for its larger than life presence.

Explore the Living Heritage of Purulia

https://artsandculture.google.com/story/PQUxONV4ui7iMw?hl=en

Purulia, a district in West Bengal is the perfect amalgamation of nature and culture. Red roads of lateritic soil cutting through dense forests, rivers and dams, hills and tiny villages paint the perfect frame and Chau dance adds the final touch to it. This exhibit gives a complete overview of Purulia, the various cultural activities and the community festivals that one can take part in or to plan your perfect getaway for the coming winter months. Get a glimpse of the quaint village of Chau mask makers, Charida too.

Through these immersive virtual exhibits, we intend to share with the world interesting stories, anecdotes, never-seen-before high resolution images of the rich cultural heritage, the visual, oral and performing arts traditions of West Bengal. Here’s to hoping that the audience will appreciate the various facets of the art form and also learn something new, something interesting about them.

Chadar Badar – Santhal Storytelling Tradition

https://artsandculture.google.com/story/4QWxZXsL60vBlg

This exhibit brings together oral traditions, songs, handicrafts and performing art skills as part of the unique indigenous puppetry of the Santhals, one of the largest indigenous communities of India, in their age-old story-telling tradition of Chadar Badar. The exhibit, launched on the International Mother Language Day, has been specially curated for commemorating this day to highlight the wealth of indigenous language and culture of the Santhals, and to emphasize that indigenous languages in all regions of the world need to be protected as they face the threat of extinction, exacerbated by globalization and the rise of a small number of culturally dominant languages. With this exhibit, Banglanatak dot com brings together its experience of working with, and reviving Chadar Badar as a hallmark intangible cultural heritage of the Santhals.

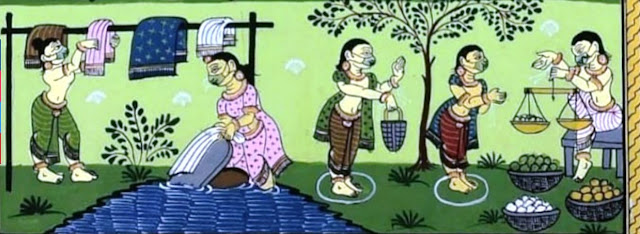

Biodiversity in Folk Art

https://artsandculture.google.com/story/2wWhiA_khzAvpw

The story is based on unique representations of the animal kingdom in folk paintings, folktales, crafts, theatre, and art of various folk artists of Bengal. The virtual exhibition showcases the integral relationship of man with nature and how creative representations of our biodiversity have continued through age-old traditions. In the story, the Royal Bengal Tiger and its various manifestations in different types of art forms is surely very interesting. The gorgeous and ferocious feline has been and continues to be an inspiration for artists. The story talks about different species of wildlife and their significance in folk culture – the tiger, the lion, the peacock, the elephant, the owl, the horse, birds and reptiles. The exhibit demonstrates the ethos of nature and wildlife conservation that have been cardinal to the lifestyles and traditional practices of indigenous communities through generations. In times when climate change, and extinction of our flora and fauna are becoming issues of major concern, the exhibit reminds the viewer of the different ways in which biodiversity merges with human life through a natural reciprocity between the two.

Indigenous Tea Makers of India

https://artsandculture.google.com/story/rgXBXxjVOWEHFw

This story is about the original tea makers of India – the Singpho and the Tangsa communities of eastern Arunachal Pradesh. The exhibit introduces the readers to the traditional tea making process of these indigenous communities, and how native tea was introduced to the British by the Singphos. It narrates the history of indigenous tea, the cultural and natural landscape of the Tangsas and Singphos, practice of indigenous tea making by the Singpho and Tangsa communities, much before the British introduced industrial tea for trading, association of tea with Buddhism and its folklore, and how indigenous tea making inside bamboo tubes is still actively practiced by these native communities. The exhibit also showcases the unique process of making smoked bamboo tea from native tea plants that can be preserved and used for many years and their tradition of drinking bamboo tea even today. Previously, the native tea used to grow wild in their hilly forest regions and they drank tea as a medicinal drink. Today, they have organized household level tea gardens from where they pluck the leaves and process to make tea. While India is world famous for its tea and has a huge share in tea business both domestic and export, it is fascinating to learn about tea in India before the British.

Exotic Weaves of Arunachal Pradesh

https://artsandculture.google.com/story/eQWBPC2C4immUw

This story, launched on the National Handloom Day, is about the women weavers of Arunachal Pradesh, celebrating their cultural heritage of loin loom weaving across different ethnicities of the state. The story showcases the indigenous knowledge, skills, and practices of such weaving by the women that is thriving even today; the process of loin loom weaving; and the different types and styles of textiles that these communities wear. Every household has one or more loin looms that are fixed in their balconies and can be folded and put away when not in use. The women, both old and young, know weaving and make their own textiles, bags, scarves, etc. The diversity of motifs, designs, and colours is quite fascinating and they distinguish one community from another, and upholds the inherent self-sufficiency and creativity of these communities.

The Land of Biodivinity

https://artsandculture.google.com/story/oQVBLDKOqd112w

Launched on the International Day of the World’s Indigenous Peoples, this exhibit showcases the lifestyles and cultures of the indigenous communities of Arunachal Pradesh – the lesser known traditions of the people who live as one with nature, venerate nature, and nurture an inherent custodianship of local biodiversity through their daily living! The story narrates how divinity in nature is a way of life of the indigenous peoples of Arunachal Pradesh and introduces the readers to the architecture, food, dress, handicrafts, faith and conservation practices of these communities that showcase their unique knowledge, and interdependency on natural resources and their local biodiversity. Arunachal is endowed with rich natural and cultural heritage embedded in the centuries old traditions of the ethnic peoples, which uniquely connect their lifestyles and spirituality with nature that can be termed as, ‘Biodivinity’. The exhibit showcases the coexistence of these communities with nature, how they nurture the richness of their natural habitats, and how their minimalist lifestyle is manifested through their indigenous architecture, technology, agriculture, food including delicacies, weaving, bamboo crafts, rituals and festivals. Although the communities featured in the story have continued to protect and preserve their indigenous knowledge and practices for generations, some cultural heritage elements are dying.

Tapestry Tales in Handlooms

https://artsandculture.google.com/story/8gWBGFhiqlDmZw

Tapestry weaving is an important cultural tradition followed in the western and eastern parts of India. This exhibit focuses on traditional weaving of natural grass, jute and cotton, as a way of life of rural communities and how simple, rudimentary handlooms are used for it. The story delves into the weaving of Madur in Midnapore districts and Dhokra in Dinajpur districts from Bengal and Durrie weaving from western Rajasthan.

Magic of Bengal Handlooms

https://artsandculture.google.com/story/HAUhYTKEkONaLg

Bengal is known for its fine and exquisite weaves. The legendary finesse of handloom textiles derived from the specialized traditional knowledge and skills of the rural weavers, have generated awe across the world for centuries. It is an elaborate and entirely handmade process that makes such textiles precious. The exhibit gives a detailed description of the techniques used for weaving and also the step-by step process followed by the communities who weave magic from yarns. The story gives a vivid narration of some of the famous weaves from Bengal like Baluchari, Tangail, weaves from Shantipur, Phulia and Kenjakura.

Exploring the Unknown

https://artsandculture.google.com/story/OAXxfh8OlPdw-A

Launched on the World Tourism Day, this exhibit showcases the lesser known or unknown offerings of cultural tourism in Arunachal Pradesh. It presents the diversity and richness of indigenous cultures of Arunachal, and introduces the readers to the actual tradition bearers, who are also the host communities (such as the Tangsas, Singphos, Khamptis, Miju and Idu Mishmis, Galos, Apatanis, Buguns, Monpas, Membas and others) managing community led tourism in rural Arunachal. The story spotlights some of the very interesting cultural experiences that a visitor can have across the state including indigenous food and beverages, smoked bamboo tea, traditional architecture, folk songs and dances, handicrafts, festivals, and the beautiful village lifestyles of the communities.

Desert Music: Soul of Western Rajasthan

https://artsandculture.google.com/story/twUBeELO1jFemw

The districts of Barmer, Jaisalmer, Jodhpur, and Bikaner of western Rajasthan are known for their deserts, forts and palaces and also for the indigenous folk music of the Langas, Manganiyars and Mirs. The exhibit, launched on World Music Day, depicts stories of these unique caste musicians by providing an informative presentation of their history, traditions, musical themes, community legends, and repertoire of their songs. The Langas and Manganiyars follow and revere their traditional Jajmani (patronage) system. Through generations they sing for their patron families and in return receive grains, animals and money. This tradition of music as a hereditary profession enriches their musical practices and repertoire. The lesser-known Mir musicians have also been included in the exhibit.

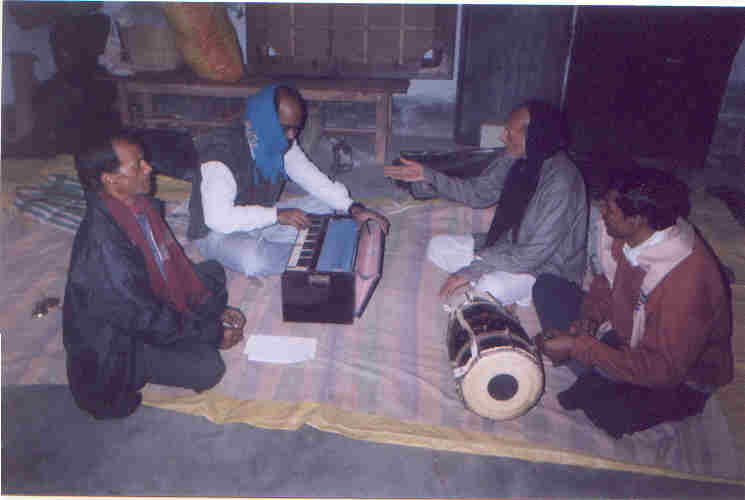

Strums and Beats of Desert Music

https://artsandculture.google.com/story/YAUxHbfg_k0gNA

This exhibit was launched on the occasion of World Music Day. The Langas and Manganiyars use traditional musical instruments that are unique to these communities and range from chordophonic (string instrument), aerophonic (wind instrument) to percussion instruments. The exhibit brings together all their traditional musical instruments (Sindhi Sarangi, Kamaicha, Khartal, Algoza, Dhol, Morchang and Murli), and information about them. One gets an opportunity to hear the musicians play the tunes and beats of the iconic instruments and learn about their cultural significance to these hereditary musicians. The story also narrates interesting anecdotes about different musicians and the instruments.

Meet the Music Progenies of the Desert Music Tradition!

https://artsandculture.google.com/story/qQUhGSu2_iR1fA

Music is something that the children of the Langa and Manganiyar communities are born with. This exhibit, launched on World Music Day, portrays how the children have an inherent sense of tunes and beats that are further developed through a Guru Shishya (master disciple) parampara embedded in their family traditions. The oral tradition is passed down informally as the children grow up listening to, and learning from their grandfathers, father, uncles and neighbours practising music. The story throws light on how the children are also passionate about learning their traditional music. One can enjoy the soulful voices of the children from the Langa and Manganiyar communities, and snippets of Guru-Sishya training in this exhibit.

Women Masland Weavers of West Bengal

https://artsandculture.google.com/story/bgUxrTu7bg_6eg

Masland or Mataranchi, made from a locally grown grass called Madurkathi is an exclusive and fine handwoven variety of Madur (mats) traditionally made by women of Medinipur region of West Bengal. The exhibit showcases the arduous process of weaving the mats and how the women are socio-economically empowered as weaver collectives and entrepreneurs. The exhibit also throws light on the intricately woven designs of Masland as well as diversified lifestyle products like table mats, bags

which are sustainable and eco-friendly. The story narrates some of the success stories of women Masland weavers, and also spotlights the intricate process of making super fine Masland from locally grown grass.

Women Painters of Rural Bengal

https://artsandculture.google.com/story/wgWhWYEU-H_prw

Patachitra is a unique folk tradition of visual storytelling accompanied by songs. In Patachitra, stories are painted as frames on long scrolls and the Patuas (the painters) gradually unfurl them while presenting the story through their songs. The exhibit shares the story of how women Patuas have painted their road to empowerment. Traditionally the men used to go around the villages singing and sharing the stories, while the women stayed at home and assisted in painting. Today the women Patuas have made their individual identities as artists, travelling nationally and internationally to showcase and sell their art. They are role models for many women in and around their village. Launched on International Women’s Day, the story narrates the journey of the women Patuas of Pingla creating their identity as artists.

Story of Goddess Manasa

https://artsandculture.google.com/story/ewXxxyq4sezQew

The story of Manasa Mangal Kavya reflects how gender constructs are challenged in folklore. Manasa is an indigenous Goddess, worshipped mainly for protection against the perils of snakebite. This exhibit beautifully narrates the story of two powerful women – Manasa, a Goddess, and Behula, a commoner. Manasa is seen as a Goddess taking vengeance to negotiate respect from a powerful merchant, whereas fearless Behula embarks on uncharted journeys to resuscitate her dead husband. Traditional craftsmanship and folklore are closely associated in community narratives. The exhibit showcases the representation of Manasa Mangal Kavya on Patachitra scroll painting, and the use of Terracotta and Shola craft in ritualistic practices of worshipping Manasa.

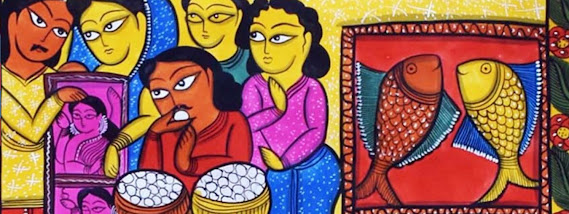

Fish Wedding Story in Bengal Patachitra

https://artsandculture.google.com/story/ZAWBnNOlbmMb8A

This exhibit, launched on the occasion of World Art Day, narrates the popular folklore of a fish wedding that the Patachitra artists, aka Patuas, of Pingla beautifully depict through their scroll paintings, songs and diverse products. The fish motif is commonly used in Patachitra paintings. This fish motif comes from the folklore of the Fish Wedding (maacher biye). Patachitra artists typically paint on various subjects – mythology, folklore, social issues but Fish Wedding story is one of their favourites. The story is about the wedding of a Dariya fish, where all the fish have been invited. The narration starts with their merry-making and feasting. Amidst all this the fishes don’t realise that danger is looming large. The Boal fish, known as a monster fish, pops up and swallows everyone because he was not invited to the wedding.The story is also interesting for its metaphorical representation of power based societal divides. The exhibit also showcases the popularity of the fish motif through its depiction on different products such as saris and home decor, as well as the GI (Geographical Indication) logo of the art form.

Holi: The Festival of Colours

https://artsandculture.google.com/story/oQXB0ggTs0eutw

This exhibit, launched on the occasion of Holi, tells stories of the different cultural aspects of this traditional festival of colours that is manifested in songs, dance, architecture and craft. The festival of Holi is celebrated across India by every region in their own unique ways. Similarly the Rarh region of Bengal (Birbhum, Bankura, Bardhaman, Medinipur, etc) is known for its different manifestations of Holi festival through folk songs, dances, rituals, and local crafts. The story highlights art forms like- Jhumur, Baul, Patachitra, Wooden dolls of Natungram, and Terracotta. It showcases the different myths and legends especially of Lord Krishna that are associated with the celebration of Holi in the Rarh region and how that has found an outlet in the cultural fabric of the region.

A Deep Dive into the Culinary Heritage of Nagaland

This exhibit celebrates the sustainable foodways of Nagaland, reflecting the shared culinary heritage across its diverse tribal communities. Central to the Naga food tradition is a deep-rooted knowledge of local biodiversity and food wisdom, showcased through unique ingredients, traditional cooking and preservation methods, and flavour-rich dishes. This digital story aligns with the 2025 theme “Local Seeds, Local Eats”, celebrating the power of indigenous crops and community-driven food cultures in shaping a more sustainable and resilient future. In this story, the sustainability of Naga food traditions is explored through practices such as sustainable farming, forest foraging, and time-honoured preservation techniques like smoking and fermentation. The story focuses on the critical role of fresh, organic produce sold in local markets connecting producers, culinary artists, and consumers. The narrative also emphasizes the nutritional richness of Nagaland’s unique ingredients and dishes.

Living Heritage Trails of Palghar

The online exhibit on Living Heritage Trails of Palghar explores the coastal escape of Palghar in Maharashtra, rich in living heritage and natural beauty. It brings together stories of diverse tribal communities of the region and introduces the key cultural hubs and art villages of Palghar where visitors can experience the authentic intangible cultural heritages of Warli painting, Bohada mask making, basketry, folk music and dance. Through this digital curation, audiences are guided into the vibrant cultural landscape of Palghar. The exhibit opens up unseen layers of Palghar’s intangible cultural heritage – from the lyrical sound of tribal music to the intricate crafts of masks and Warli paintings offering the online visitors an immersive journey through visuals, stories, audio-visuals, and interactive elements.

Sohrai – The Wall Art of Jharkhand

Sohrai painting, a traditional art form practiced by women from various indigenous groups such as the Kurmi, Santal, Munda, Oraon, Agaria, and Ghatwal, originates from the villages in the Hazaribagh region of Jharkhand, India. The practicing communities paint the walls of their houses to show reverence and gratitude for the agricultural produce and the livestock. The exhibit showcases this vibrant living tradition of murals, nurtured for centuries by the indigenous communities highlighting the rich indigenous aesthetics and ancient motifs rooted in Mesolithic rock art found in the region. The digital story narrates the intricacies of the wall art, the rich natural landscape, where this tradition can be found, the craftsmanship of the indigenous artists and how the wall art is integral to the harvest festival.

Jadupat: The Living Arts Tradition

This is an online pocket gallery exhibition of Santhal Patachitra, an indigenous visual story-telling tradition. Published on the International Translation Day the exhibit of paintings unveils the many faces of humanity. Translation opens up a world of human experience and fulfills the constant urge to understand the other, especially the unknown cultures. Santhal Patachitra has been an age-old way of translating and communicating the intrinsic narratives of life and life after death of the Santhal culture. This folk art form beautifully entwines the visual language of story-telling with the oral tradition of songs to sustain the Santhal language orally, much before it was written down by Bengali, Oriya and other Roman scripts, and thereafter the Santhal Ol Chiki script itself.

Discover more on Google Arts & Culture: https://artsandculture.google.com/partner/banglanatak

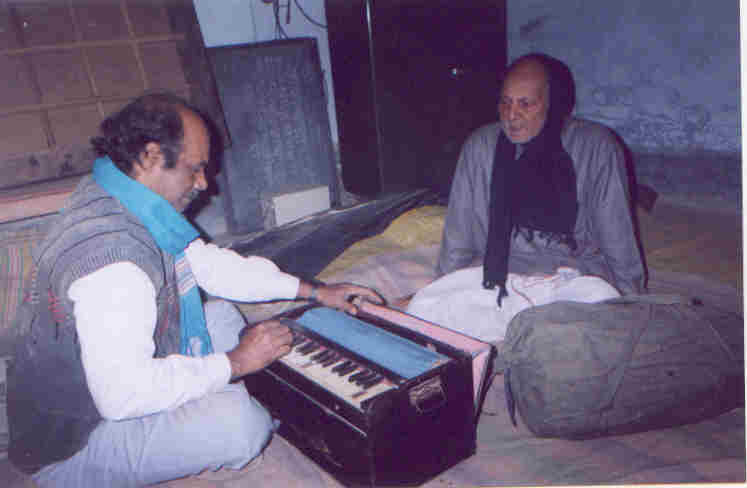

Among them, Dokori Chowdhury holds a place of pride. A gifted singer and lyricist, he inherited the legacy of legendary performers Jogendra Chowdhury (Mator) and Debnath Ray (Habla), and carried it forward with sincerity and brilliance.

Among them, Dokori Chowdhury holds a place of pride. A gifted singer and lyricist, he inherited the legacy of legendary performers Jogendra Chowdhury (Mator) and Debnath Ray (Habla), and carried it forward with sincerity and brilliance. question injustice and corruption. His ability to make Gombhira contemporary while retaining its traditional essence was remarkable. In recognition of his contributions, he received the Lalon Puraskar.

question injustice and corruption. His ability to make Gombhira contemporary while retaining its traditional essence was remarkable. In recognition of his contributions, he received the Lalon Puraskar. Jiten was not only a skilled actor but also an accomplished singer and dancer.

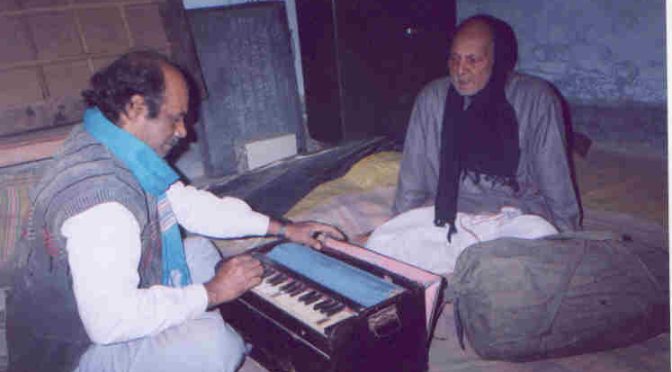

Jiten was not only a skilled actor but also an accomplished singer and dancer. His mentor was the eminent folk art specialist Subodh Chowdhury, under whose guidance Jiten refined his craft.

His mentor was the eminent folk art specialist Subodh Chowdhury, under whose guidance Jiten refined his craft.

i for his role in protecting the authenticity of Chau and opposing its distortion. He performed in countries like Sweden, Canada, France, and Switzerland, captivating global audiences with the fierce beauty of Chau.

i for his role in protecting the authenticity of Chau and opposing its distortion. He performed in countries like Sweden, Canada, France, and Switzerland, captivating global audiences with the fierce beauty of Chau. classical music—an artistic tradition in his family—he defied convention by embracing the folk form of Jhumur, guided by the renowned artist Ramkrishna Ganguly.

classical music—an artistic tradition in his family—he defied convention by embracing the folk form of Jhumur, guided by the renowned artist Ramkrishna Ganguly. Mihirlal played a pivotal role in reviving solo Jhumur singing, proving that the form could stand powerfully even without dance accompaniment. His deep voice, lyrical sensitivity, and contemporary themes made Jhumur relatable to new generations. His compositions ranged from spiritual tales of Radha-Krishna to environmental and social themes.

Mihirlal played a pivotal role in reviving solo Jhumur singing, proving that the form could stand powerfully even without dance accompaniment. His deep voice, lyrical sensitivity, and contemporary themes made Jhumur relatable to new generations. His compositions ranged from spiritual tales of Radha-Krishna to environmental and social themes.

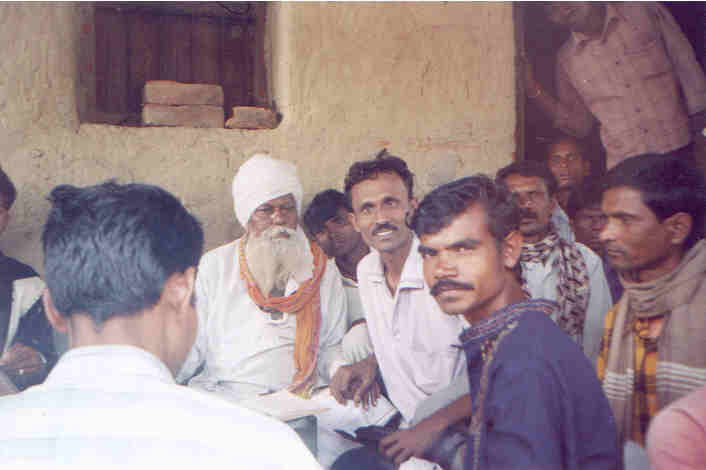

Salabat Mahato was both a Guru and a guardian of Jhumur’s authenticity in the modern era. Born into a humble farming family in Latpada village under Barabazar police station, Salabat was a gifted lyricist, composer, and singer whose influence reached far beyond Purulia.

Salabat Mahato was both a Guru and a guardian of Jhumur’s authenticity in the modern era. Born into a humble farming family in Latpada village under Barabazar police station, Salabat was a gifted lyricist, composer, and singer whose influence reached far beyond Purulia. His contributions earned him accolades like the Abbasuddin Award and the Lalon Award from the Government of West Bengal. A short film was made on his life and work, attesting to his stature in the cultural world.

His contributions earned him accolades like the Abbasuddin Award and the Lalon Award from the Government of West Bengal. A short film was made on his life and work, attesting to his stature in the cultural world.